The Netherlands - Off the shelf

In 2008 an editor from a publishing house asked me if I wanted to make a book about the Netherlands. The country had changed so much over the past 30 years; so much had been built. I understood what he meant. Walk out of the station in Amersfoort or Leiden if you haven’t been there for 30 years and you’ll get the fright of your life. Real estate architecture, paid for with money from pension funds, is everywhere. And that is just the beginning. Housing developments, industrial estates, shopping malls – so much has gone up in recent times. The prospect of photographing it all didn’t strike me as a pleasant one.

I did want to make a book about the Netherlands. For me, it seemed more obvious to revisit a series that I had made earlier. In the summer of 2004, I spent a month travelling through the Netherlands for an assignment for NRC Handelsblad. For the back page of the newspaper I wrote a column every day to accompany a photo I had taken. The series was published later that year as a book called Achterland (Hinterland).

Surprise at the layout of the country was a recurring theme in the book. However, the daily deadline meant I didn’t have the time to process all my impressions.

When I picked up the thread again in 2008, I took the opportunity to look around at my leisure. I drove to Nieuw-Vennep, parked the car and walked around with a stepladder that I always have with me for a slightly elevated perspective. In Venneperstraat I took a photo of two women who had struck up a conversation. One was bent over her bicycle; the other was standing next to a pushchair carrying a toddler. The basket under the child was filled with groceries. To the left and right of them were low-rise shop premises from the 1960s and further along the street were older houses. The scene gave nothing away about the exact location, but it was unmistakably photographed in the Netherlands.

I instantly liked the form of the photo. It allowed me to show what the Netherlands looks like in places like these. The ladder offered a slightly better overview and sense of space. It emphasises the idea of construction, of a glimpse of a spectacle. It is as if you are sitting in a seat in a theatre and the trees, church tower, bottle banks, houses, shops and street furniture are part of a set.

It became clear to me that I had to visit places that were not too large; where you meet people on the street, but not too many. They are not passersby, like in cities, but generally people from the immediate vicinity. They are a natural element of the picture.

Moreover, the small proportions make it easier to show the absurd combinations of architectural styles next to one another. The centres of many municipalities are a patchwork of additions that have been made over time. That is what gives them their typical character. You find a grand, 19th-century building next to an electronics shop with a flat roof from the 60s. Next to that is a low-rise dike house from the 20s and a branch of Rabobank less than a decade old.

It is an environment where regulations and coincidence determine the picture, where you find the latest ideas on the design of a square against a backdrop of local middle-class architecture. Attempts at control are literally a reflection of different interests and opinions.

As I had in the mid-90s with Hollandse Velden (Dutch Fields) - a book about amateur football in the Netherlands - I felt that I shouldn’t be in the premier league but lowlier places, in this case away from an urban setting. Like Dutch Fields the result is a sparser image of a culture, which I believe gets closer to its essence. It shows a great familiarity and interchangeability and thus something of the mechanism that manifests itself differently in every culture.

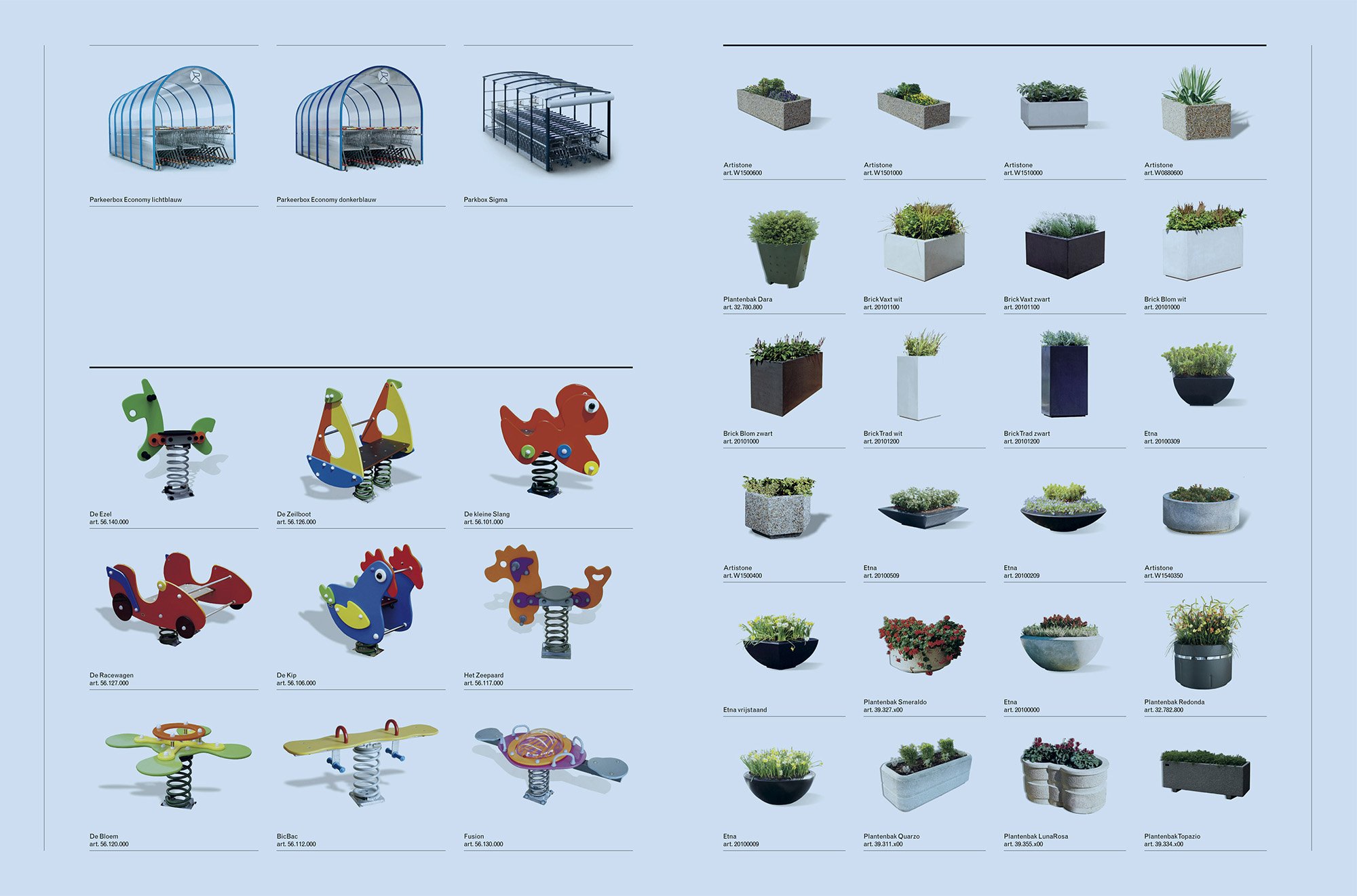

In one of the columns in Hinterland I described in part how this mechanism works. For example, if a square somewhere has to be redesigned the architect picks up the catalogue of a company specialising in street furniture. ‘He chooses some benches and rubbish bins and looks for a matching grille for the trees,’ I wrote then. The catalogue at the front of this book illustrates that idea. Everything we see around us can be ordered and delivered.

The same applies to the cafe and restaurant interiors included in this book. Despite the great variety, like the street scenes they are in many cases unmistakably Dutch. Increasingly, however, you see that the appearance and atmosphere are not the result of the originality of owners who have put their stamp on the interior over a period of years. The appearance is a concept that people consciously choose and for which the corresponding props are ordered from a wholesaler. Flick through the catalogue and you will find the pavement signs that the baker or butcher uses to convey his traditional craftsmanship. But those signs, which are not produced using any traditional methods, are everywhere. It illustrates the disconnect of our time.

Therein lies a significant distinction in what we see around us; between culture from a time of traditional thinking that has been formed over many years and mass-produced culture that can be ordered at any given moment.

The latter is less about who you are and more about who you want to be. This is evident not only in a cafe’s decor, but also in the design of a square or a street. The need for authenticity and identity is apparently so great that a kind of off-the-peg industry has been created which meets this demand and always has the individual parts in stock. Funnily enough, that inevitably has the opposite effect: everything starts to look the same again.

When we come back from a holiday abroad it is immediately obvious when we have crossed the border. This is the Netherlands; this is the way we do things. Why we do them this way remains a puzzle.